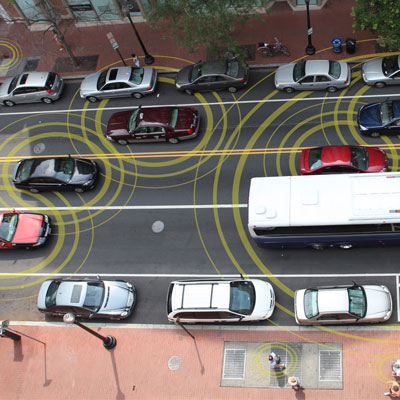

The Trump administration appears to be pumping the brakes on a mandate that would have required automakers to install vehicle-to-vehicle communications devices in every new car or truck. “Connected cars” are coming, and they hold enormous, even life-saving potential — yet we should applaud this latest development.

Paradoxically, mandating connected cars — especially just one, government-designed device — will only hold back a still-experimental technology.

With the clock ticking down on the Obama presidency, and before the incoming Trump administration could stop them, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration proposed to mandate so-called dedicated short-range radio communications devices in December 2016. According to the Associated Press, some in the Trump administration would like to shelve the proposed mandate because of its high cost — NHTSA estimates initial device costs will be about $330 per vehicle — and uncertain benefits.

Connected cars are nothing new. For years, automakers have offered GPS, services like OnStar, sensors for hazard warnings, and Wi-Fi access or infotainment services like 4G LTE. Wireless technology has advanced and today some car companies are testing out complex vehicle-to-vehicle and vehicle-to-infrastructure technologies. If they work well, these new devices will alert drivers and (someday) autonomous vehicles in real time to potential collisions, traffic jams, and dangerous weather conditions that are not detectable by existing sensor-based technologies like lidar and radar.

Technology vendors and car companies around the globe are racing to develop safe and reliable systems. However, if NHTSA’s December proposal to mandate its favored technology — DSRC — survives, it threatens to short-circuit the competitive process.

Until now, NHTSA has never required that vehicles include any communications technologies. But DSRC has received substantial government investment since 1999, when the Federal Communications Commission set aside spectrum for the service.

The truth is, despite the free spectrum and years of Department of Transportation funding, DSRC technology is far from roadworthy. When the FCC codified most DSRC standards in 2004, DOT officials told reporters to expect commercial deployment in 2005. But with only marginal automaker interest for over a decade, NHTSA now sees a mandate as the only way to jumpstart this particular technology.

The disinterest on the part of automakers is likely due to documented problems with DSRC reliability. A May 2016 report from Booz Allen Hamilton researchers produced for the DOT, for instance, found that “the system will be able to reliably predict collisions only about 35 percent of the time.” False alerts were a particular problem in a test pilot. Alarmingly, even one second before a sure (simulated) collision, DSRC units only detected it 80 percent of the time. Since drivers need three or more seconds to respond to a collision warning, the researchers concluded that the error rate “draws into question the safety integrity of the system.”

The truth is, despite the free spectrum and years of Department of Transportation funding, DSRC technology is far from roadworthy. When the FCC codified most DSRC standards in 2004, DOT officials told reporters to expect commercial deployment in 2005. But with only marginal automaker interest for over a decade, NHTSA now sees a mandate as the only way to jumpstart this particular technology.

The disinterest on the part of automakers is likely due to documented problems with DSRC reliability. A May 2016 report from Booz Allen Hamilton researchers produced for the DOT, for instance, found that “the system will be able to reliably predict collisions only about 35 percent of the time.” False alerts were a particular problem in a test pilot. Alarmingly, even one second before a sure (simulated) collision, DSRC units only detected it 80 percent of the time. Since drivers need three or more seconds to respond to a collision warning, the researchers concluded that the error rate “draws into question the safety integrity of the system.”

DSRC has a long way to go. A mandate would be unprecedented and dangerously hasty, especially as new, competing and complementary technologies—like cellular-based devices and lidar sensors—advance and gain adoption.

Mandating that all new vehicles include DSRC risks locking in an inadequate and unsafe technology. As we’ve seen with some past FCC device mandates, dead-end consumer technology can live on, zombie-like, for years or decades after the market has moved on.

Rather than compel automakers to add costly DSRC systems to cars, NHTSA should consider a certification or emblem system for vehicle-to-vehicle safety technologies, similar to its five-star crash safety ratings. Light-touch regulatory treatment would empower consumer choice and allow time for connected car innovations to develop.

In the fast-moving connected car marketplace, there is no reason to force products with reliability problems on consumers. Any government-designed technology that is “so good it must be mandated” warrants extreme skepticism, and Transportation Secretary Elaine Chao should continue to treat the Obama administration’s Hail Mary with caution.

Brent Skorup is a research fellow in the Technology Policy Project with the Mercatus Center at George Mason University.